“My favorite moment in life is not knowing where a conversation is going to go.”

— Paula McAvoy

I wrote that down while Paula was telling a story of an unexpected conversation she once had in a northwoods Wisconsin supper club. She was on a panel at NAAPE 2024, responding to Sarah Stitzlein’s 2024 book "Teaching Honesty in a Populist Era: Emphasizing Truth in the Education of Citizens.”

Feeling uncertain about the direction of a conversation but heading there anyway is just so fun. We love a good conversation here at the Center for Ethics and Education. Today’s newsletter, all about conversation, was written for you by Ria Dhingra, our CEE Postgraduate Fellow (and a terrific conversationalist).

—Carrie Welsh, CEE program director

……….

What is Good Conversation?

by Ria Dhingra

“Ah, good conversation — there's nothing like it, is there? The air of ideas is the only air worth breathing.”

― Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

I’m still thinking about that line from Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, which I (an English major) finally got around to reading last summer. It’s both a biting critique and a nostalgic elegy for late 1870’s high class New York Society.1 The novel explores feeling trapped by convention and emotional repression. It’s witty and acute in its narration. I found myself laughing and later moved to tears; I cannot recommend it enough.

To me (also a philosophy major), there is nothing better than a good conversation. Good conversations feel more important than ever right now. But what is a good conversation? Is it fun? Fast paced? Philosophical? After all, “there’s nothing like it.” To a philosopher, one who lives in the world of ideas, “it’s the only air worth breathing.”

So, today’s newsletter will explore: what constitutes a good conversation?

Contents:

Listen to a short conversation between two good friends

Philosopher David O’Brien on not being a wizard with all the answers

Good guides for navigating college

Harry Brighouse on the dinner party magic of assigned seating

Tennis and Time Travel: Conversation Chemistry

by Ria Dhingra

My favorite conversations are where you lose track of time and get lost in a series of overlapping tangents. Wanting to stay after class to continue questioning a reading. The phone battery dying in the middle of a late-night phone call.

In a newsletter about conversation, I thought it only made sense to share some audio! Recently, I sat down with one of my favorite conversation partners, CEE Undergraduate Fellow and dear friend, Teresa Nelson, to have a conversation on the nature of conversations. We discuss making friends in discussion sections, reading Lorrie Moore, and what to do when you find yourself in a bad conversation. You can listen to it here:

Conversations Do Their Own Thing

with philosopher David O’Brien

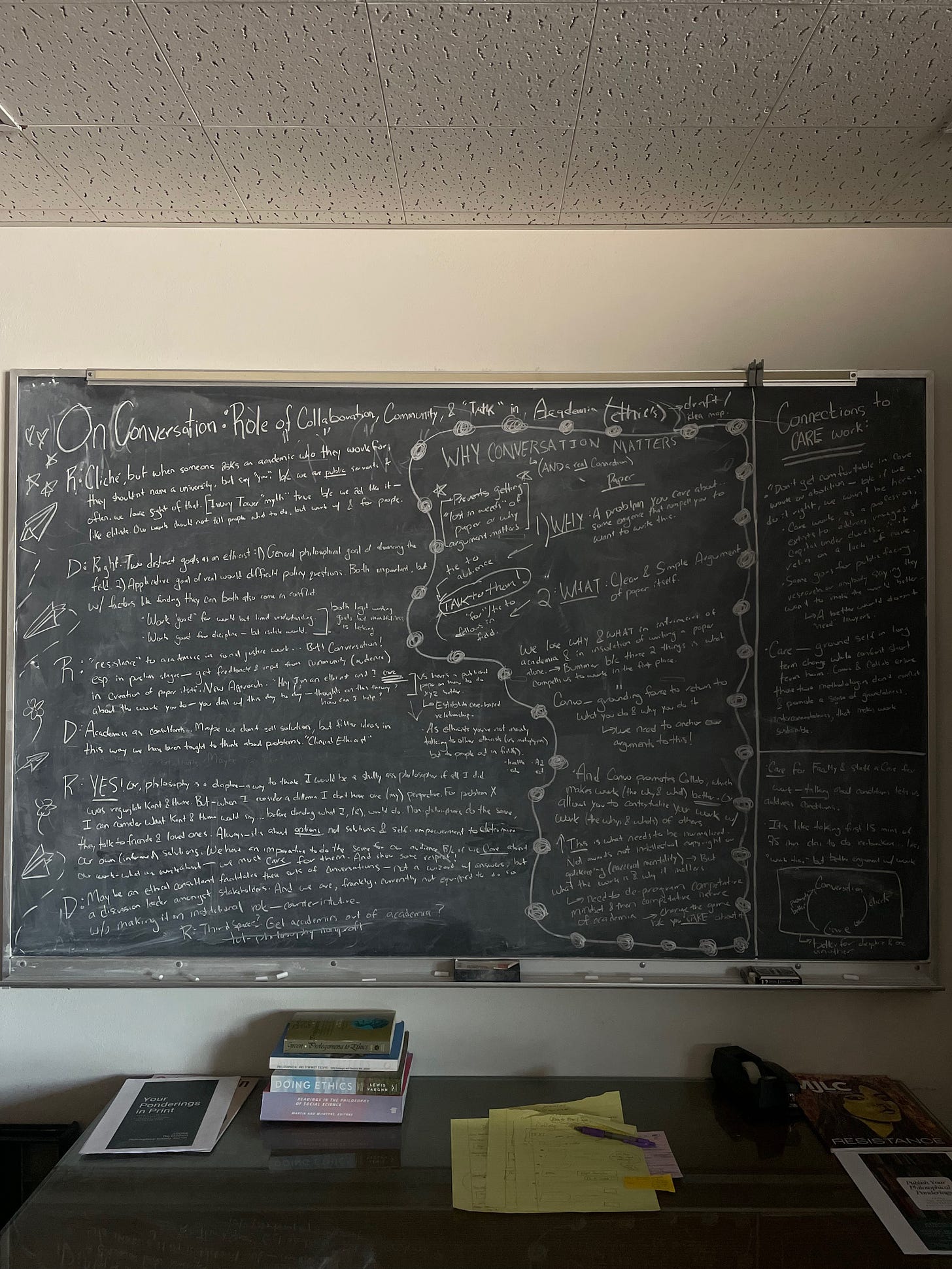

At NAAPE, I (Ria) started a great conversation at a works-in-progress session with David O’Brien about his latest paper. I stopped by his office in early December to continue our conversation, which touched on the topic of incomplete papers, the necessity of academic collaboration, the social role of a philosopher, and trust circles for feedback. David O’Brien is an Assistant Professor in the department of Educational Policy Studies at UW–Madison.

Here’s an abridged version of our chat:

R: Let’s start with the paper you brought to the work-in-progress roundtable. Could you remind me what the title was? And could you briefly describe the argument?

D: Sure thing. Funny, I’ve actually forgotten the title! I think that version of the paper was called, “How To Be A Luck Egalitarian About Justice In Non-Ideal Conditions” which is a very unwieldy title.

R: Like most philosophical papers.

D: Like most philosophical papers [laughs]. But the basic idea of the paper was pretty simple: the view about justice that I find quite plausible is one that sets a really high bar. It tends to say that if there is any existing inequality that impacts the flourishing of two lives, then that’s unjust. And that’s really demanding. There are lots and lots of inequalities like that. So, in education in particular, if that is the correct theory of justice, that is going to demand so much of us. So, the question I was interested in for that paper was: given how high that bar is, is there any way we could get out of imposing such demanding requirements on us? And my thought in the paper was, if someone else prior to you (in the past) has left you with a very difficult choice situation, an unjust stating condition, then maybe this theory of justice is not so demanding.

R: Tell me more about how you developed this idea.

D: It’s a relatively new idea for me, about a couple months old. I was talking to friends of mine who were working on other theories of justice. And, in the context of those theories, these questions about non-ideal theorizing (what a theory of justice demands of you when other people have left you in a difficult choice situation) is very prominent in discussion. And I got interested because if those people have a lot to say about that non-ideal question in their work, why shouldn't I be thinking about it in my theory of justice tied to education?

R: Now that you’ve presented the first draft, what’s the direction of the paper moving forward?

D: A lot of times when you are doing philosophy presentations, you’ve basically done all, if not all of the thinking, before you present it to others. But that NAAPE roundtable was the first time I have ever presented the idea of a paper at such an early stage. So, more than usual, it helped me think about possible future directions of the project.

Two things really stand out to me about that roundtable session. First, as with lots of things when you start writing, you get very in the weeds of your own argument and you sort of focus on one little bit of the argument that is often several steps down the line. But the conversations in that session helped me remember how to talk about the big picture of an argument. I needed to present the basic idea in a way that would make sense to people hearing it for the first time.

The other thing–a big thing–that came out of those conversations was actually talking to you, Ria. Before the roundtable, I had basically been thinking in a very naive or perhaps simple way about the basic problem I was interested in. I was considering: What should we say when some other person leaves us in a situation where our individual choice is now harder? And the thing that you put in my mind, which hadn’t been there before, was what if it’s some social institution, not an individual person, that leaves us in the more difficult choice situation? So, the future direction of the paper is focusing much more on that institutional aspect.

R: I think what excited me most about your argument and our conversation was how it could potentially provide student groups and graduate student unions the philosophical foundation to hold an institution accountable for the non-ideal conditions we must now navigate. I was really involved in student movements as an undergrad and I thought about this a lot. Oftentimes, in those sorts of negotiations, you see TAs and graduate students listing out, “This is what I think is unfair” (pay, hours, etc.). But now, with a paper like this, you’ve given them a philosophical justification where they can basically say, “looking at the theories of justice, I am now in a position where I am expected to do more moral labor at a higher cost (burden) to myself based on your failings…and maybe we are not responsible for picking up that burden.” Now, that burden is up in the air and it negatively impacts students. Obviously that’s a really philosophical way of saying it, but laying out that kind of argument to the institution itself might lead to more productive interventions. The implications of this paper are just so exciting in terms of eliciting institutional change.

D: Thank you. And this is why I think work in progress talks are so valuable. When you present a fully formed paper or idea, the conversation after is more about accepting or critiquing that idea. But discussing an idea at a more embryonic stage results in more creativity regarding implications or applications of the argument.

R: Like you said, I feel like writing a paper means getting “lost in the weeds.” But before grappling with an argument, there is an exigence that prompted you to write it. (The why.) And then there is that clear and simple basebones of the argument itself. (The what.)

I feel like those two elements, the “WHY” and the “WHAT” often get lost in the intricacies of academia and the isolation of writing a paper alone. Which is a bummer because the “WHY and the “WHAT” is what makes this sort of work so important in the first place. Collaboration, talking to people about what you are doing and why you are doing it, is almost a grounding force that returns to those two elements.

D: I think you’re absolutely right. In the real world, an important impact that philosophy can make is this exact sort of thing. Philosophy can give people some language or tools to assert a firm judgement that they might have. (Ex: articulating unfairness in working conditions for educators). A genuinely good thing I think philosophy can do is empower people, make them feel confident to use philosophical arguments about justice and equity and whatever else in the everyday.

Keeping the usefulness in mind during the writing process can anchor the argument to something real, something important, something larger than the writer themselves.

R: That’s so interesting. I just started working as a communications writer. Which is very different writing than the academic philosophy papers I am used to. Here, I think about the audience a lot. How can I put a story or words into a way that is accessible and useful for this larger “public”? Which is, funnily, the reason I loved this branch of philosophy so much. As ethicists, we’re talking about philosophy - to people not in philosophy. Our primary audience isn’t the academic community, not really.

D: I think that’s right. There are two different goals. And it’s good to keep both of them separate in your mind and they are both important. The general philosophical goal of understanding what you are thinking and advancing the collective thinking of the field. Then there is the applicative goal of helping real world people who are engaged in difficult policy questions.

In principle, there can even be conflicts between those goals: work that is good for the public but limits philosophical understanding, or work that is good for understanding but so isolated from the real, everyday, world. That being said, I think both are perfectly legitimate writing goals. Some works can do a bit of both. Maybe that’s being too kind to myself. [laughs]

R: No, but I think that’s true! I think what’s so exciting about preliminary conversations with a paper’s target audience is getting input, feedback, and collaboration in the creation of the paper itself. Rather than I, the philosopher, telling you what to do about healthcare or AI or education, conversation allows for the approach of “hey, I’m a philosopher and I deeply care about these issues and I know you on a day-to-day work within this field…what do you think about this theory I have?”

D: You can even take this one step further and imagine ways that philosophers (or academics generally) can interact with the people not primarily focused on academics. Beyond sharing works in progress, perhaps having this broader different kind of conversation about the role of academics as consultants… not as a wizard who has all the answers, but as someone who prompts critical conversation, could be interesting.

R: On that note, what do you think the role of conversation and collaboration looks like within the field of philosophy itself?

D: I can tell you what that looks like in my life. I tend to think of the role of conversation in my work to happen in two stages. One, I have a very early idea. And I’m not at all confident that it’s going to turn into anything. So, I have two or three people that I trust enough to be vulnerable with to express those thoughts. Then, the most common time for feedback and discussion is when I present a finished paper. In that adversarial set up, I get critiques and try to defend my paper while also taking note of them.

So, in my mind, those are the two stages of conversation. A small scale one that requires a lot of trust and vulnerability and then the kind of outward facing talk. Both are really valuable. I think my life would suck without these sorts of talks. But they each feel so different to me.

R: Total sidebar question, but how did you find those 2-3 people you feel so comfortable with? As a younger academic, I would really love to have support like that.

D: It’s hard and rare. It does feel like a gem. It was honestly luck. And then history. My “people” I found during grad school. Which is a time where you are all in it together; you have seen one another grow and make mistakes in a way that builds trust. Now, as an adult, meeting people at a conference, forming that level of an intense relationship definitely feels harder.

R: You teach philosophy of education. How do you promote that level of collaboration or relational intimacy amongst your students? Or create that sort of trusting environment?

D: I actually think a lot about this. I do what I can to promote collaboration amongst undergraduates, partly because it’s been so valuable for me. For example, I try to structure discussion where conversations about objections to an argument are practiced as a collective exercise. In this case, I like to think that the classroom discussion is raw material for papers. The writing is independent, but the thinking is collective.

The more general thing that I think you’re getting at, which sounds like common sense, is that conversations, perhaps, cannot be separated from the relationships they come from. A danger in philosophy, both in research and in teaching, is that we think we can do the conversational work without the relational work that elicits that deep intellectual collective curiosity. The really productive and valuable conversations happen when you know people. It seems simple: How you’re disposed to react to other people depends on how well you know them, how free you are able to be.

R: That makes me think of how Professor Brighouse starts class with an icebreaker every session, all semester, and makes each student answer individually. It leads to us all knowing each other by the end of it. But now, in the context of us speaking, it seems as if Harry recognizes and acts on the idea that: if good class conversation is predicated on good relationships, icebreakers are essential.

D: Right, that tradeoff of fostering relationship versus using up your teaching time for content. Harry leans into it so intentionally. A shorter class with better conversation versus a longer class with more content. This is why both teaching and research is so hard—it depends on so many circumstances with a limited amount of time.

R: Thanks so much for taking the time to have this conversation with me today.

D: Thank you. Like most people, I typically get up in the morning and just “do” my work. Stepping back like this and thinking about the nature of this work and the kind of conversations I get to have feels like an important reminder as to why I do it.

R: That’s really wonderful. I'm amazed at all the directions we just launched into!

D: Yeah, I’m so surprised. Conversations do their own thing!

Two Guides for Navigating College

As undergrad philosophy majors, we spent a lot of time talking about philosophy. Both of these guides came out of good conversations we had with others:

Tips for Writing Philosophy Papers: What I Wish I Knew From The Beginning

by Anna Nelson (former CEE Undergraduate Fellow)

Know your assumptions. Before you even begin crafting an argument, think about your own assumptions and then label them. This is really helpful when you have case studies or thought experiments. It’s a good way to start thinking and will keep you out of trouble later!

Define your key terms. Don’t assume everyone is going to have the same understanding of “socialism” as you. Philosophy is about questioning everything and taking nothing you know for granted. It’s okay if there are different interpretations of terms or arguments, just make sure it’s clear which ones you’re adhering to.

Outline. I like to start with a solid outline before I write to ensure my argument is clear. Then I sort of expand it from there until it becomes an essay.

Spit it out. Put your argument and what you’re gonna say right at the beginning, lay out what you’re going to do and create a road map for your argument.

Objections. Always include an objections section at the end! Note what the strongest objections to your argument could be and respond to them. Don't waste space on the weaker objections unless you can do it succinctly.

Co-author papers if you can! Or just expose your ideas to other people who are willing to chat. Finding people you disagree with leads to the best outcome.

…

Tips for Coming Into College (Philosophy or Otherwise)

by Ria Dhingra and Ari Collins

Take classes with friends. Talk about class outside of class. Talk about class as you walk into the room and as you walk out of it. By making concepts something you consider in conversation, you not only build relationships with people, but understand the material a lot better.

When taking notes, don’t just write down what is on the board or what is being said. Note-taking isn’t about copying, but engaging. Personally, I write my own ideas, objections, and questions in a different color in the margins next to my notes. That way, when studying or writing a paper, I know what I thought about the material in the moment.

Get your tuition’s worth! Attend every on campus talk and lecture series. (Plus, most events have free food and coffee!) Sit in on a cool class you wanted to take that didn’t fit in your schedule. Email that professor and ask to meet outside of class.

Give people grace in class and in discussion sections. Articulating your thoughts immediately as you start to form them is always a recipe for disaster, but a requirement for most discussion based courses. Recognize these circumstances and realize people’s opinions and ideologies grow and change from rigorous conversation.

Telling People Where to Sit

by Harry Brighouse

At academic professional events, I really like assigned seating. Here's why.

If I'm sponsoring a social event I generally have a purpose for that—which includes facilitating certain kinds of networks and especially networks in which more experienced scholars are more likely to support and mentor more junior scholars.

However, like any profession, academia is characterized by both status hierarchies (which often reflect age and experience) and friendship networks (which also often reflect not only age and experience, but also institutional affiliations). So if people choose where to sit, they are likely to sit with people they already know, who are similar in status, age, experience, and already in the same networks.

There's nothing wrong with that, but it works against my aims. Assigning seating so that each table has a mix of status, age, and experience helps achieve my goal: conversation amongst strangers. It also removes some of the awkwardness that younger and more junior scholars often feel, wondering whether it is okay for them to sit near someone older who they would find interesting to talk with.

Ria’s Recommendations

Teresa Nelson on learning through conversation in last February’s newsletter

The classic 36 questions to create closeness with someone (developed by Arthur and Elaine Aron in 1997 for a study called “The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness”)

This great interview with Ian Williams on the art of conversation:

“I think a good conversation reaffirms human potential: that if I extend myself toward someone and they extend themselves toward me, this whole human enterprise feels worthwhile. A good conversation can make you feel hopeful that everything is going be OK with the world. It’s energizing.”

The “Which Vegetable Are You?” quiz (we did this with our curriculum team)

Literally any interview from any issue of The Paris Review (here’s an “Art of Fiction” interview with Jhumpa Lahiri that Ria and Carrie both love)

Our episode on Learning Through Conversation with Agnes Callard:

Thanks for reading!

Keep in touch,

Ria Dhingra and the Center for Ethics and Education

(ed. note: And a great 1993 movie starring Winona Ryder, Daniel Day-Lewis, and Michelle Pfeiffer)

Hi I’d love a read as I dive into the ethics of tech through the lens of Japanese animation

https://open.substack.com/pub/davidfoye/p/akira-and-the-ethics-of-technological?r=4g90ob&utm_medium=ios

Hi

I have initiated “CAN FICTION HELP US THRIVE” to empower writers who create fiction with an overarching sustainable vision.

My book, “The Jacksons Debate,” is published under this banner.

It explores the ethical complexities of interspecies relations through the lens of an advanced alien civilization called the Jacksons. The novel challenges readers to consider how easily a more advanced civilization might view humans as a resource, mirroring humanity’s own treatment of other species on Earth.

It can be found here — https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/228994545-the-jacksons-debate