Conceptual Optometry

Stealing crisps and learning through conversation

Happy February, everybody. Here in Wisconsin, we’re navigating weirdly warm weather and are excited about our spring projects: putting the finishing touches on our Touchy Subject teaching guide, working on a new episode about the ethics of mentoring, and presenting at the EPS Conference next month.

—Carrie, CEE program director

In this newsletter:

Icebreaker: Zoom emojis

Philosophy of education: Conceptual optometry

Student post: Learning better through conversation

News & Events: A webinar, a case writing course, and a call for proposals

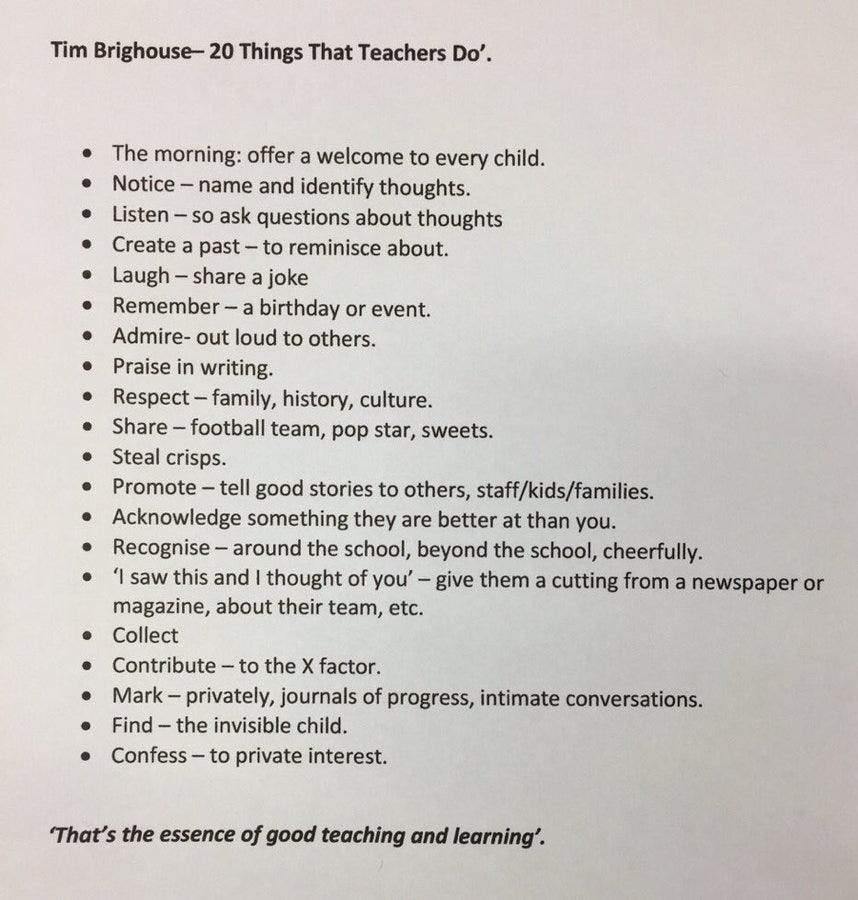

We’re dedicating this newsletter to Harry’s dad, Tim Brighouse, a respected and influential educator.

Icebreaker

We used this in our zoom-based camper book club, where we’re reading Christopher Martin’s The Right to Higher Education (2022).

Which emoji illustrates how you were as an undergrad?

Responses included: 👽👼😎😴😏

We also have a podcast episode with Christopher Martin.

Conceptual Optometry

by Tony Laden

When I first started working in the philosophy of education, I found myself having to explain to education researchers why they should care about what I did. Many of them thought philosophy couldn’t be of any use to them. Philosophers have our heads in the clouds, deal with abstracta, and are generally uninterested in or ignorant about the problems and questions they are trying to answer. Those who did think philosophy might be useful to them tended to think that philosophy produces “theories.” They wanted to apply such theories to the subject they studied to generate judgments: Applying “Rawlsian justice” or a “capability approach” would tell them whether a school funding mechanism is just. I think philosophy is useful in a different way, however, and in trying to explain that, I came up with the metaphor of “conceptual optometry.”

Just as an optometrist diagnoses which corrective lenses adjust your vision in ways that allow you to see certain things more clearly, philosophers examine and evaluate the concepts we use to make sense of the world. In doing so, we try to understand how the particular concepts we use disclose certain things more clearly while possibly obscuring others. Understanding and distinguishing concepts, and making clear what they reveal and what they obscure has practical value without offering theories. Thinking of equality in terms of sameness of treatment rather than in terms of equal levels of resources or as the lack of hierarchical relations where some are subordinated to others will draw our attention to some features of schools and society and lead us to ignore others.

One of the ways that well-meaning people go wrong in the policies or practices they advocate is by failing to appreciate how their conceptual lenses have obscured aspects of a problem they were trying to solve. Philosophy can be helpful in such situations in not only offering new conceptual lenses but in showing clearly what the lenses being used illuminate and what they obscure. Like corrective lenses (and unlike theories), the value of particular concepts is tied to what we want to use them for. Just as I may need one set of lenses for reading and another for seeing into the distance, we may find certain concepts better suited for certain kinds of investigations and others for others, in large part based on what they bring into relief.

So, the next time someone asks you (the philosopher) why they should care about what you do, pull out your lenses and show them what they are missing. And the next time you (the education researcher or teacher) feel like the world isn’t making sense, giving you a headache, or you aren’t seeing clearly, go find a philosopher and see if they have some new concepts to offer you.

And when you have found a way to bring what you want to see into clearer focus, we can talk about frames…

—

Tony Laden is the Associate Director of the Center for Ethics & Education and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Tony Laden on conceptual optometry. Filmed at NAAPE 2022 by Anna Nelson.

Learning Through Conversation

by Teresa Nelson

As the first week of February doled out stretching blue skies, forty-degree weather, and warm sunshine, my homework continued to ominously pile up. However, I ended up choosing procrastination (and therefore fleeting, momentary happiness), and took to the interurban paths of Madison to walk. I listened to “Learning Through Conversation,” an episode of our Ethics & Education podcast, and found myself thinking about my own current experience as a college student.

In this episode, our program director Carrie Welsh has a chat with philosopher Agnes Callard about conversation as a pedagogical strategy. I got to know Socrates a bit better. Apparently, according to Professor Callard, Socrates had a persistent (and sometimes irritating) style of asking questions. A key element of this style was Socrates’ ability to skillfully orchestrate stimulating conversations with his students. According to Professor Callard, conversations are so invaluable to education because it is in conversation that one may effectively face and engage with opinions that truly differ from their own. I agreed with this. A conversation is wonderfully mysterious: we simply cannot know what or how another person is thinking until we ask.

In philosophy, good conversations rely on good questions. Professor Callard explains that the key to asking a good question is that you have to really want to know the answer. I learned this in my first philosophy class.

When I came to this university as a freshman and signed up for a philosophy class, I thought it would be an “easy A,” and essentially a history class centered around the thoughts of ancient men. I was correct about the former, but certainly not the latter. Don’t let me be misunderstood: I am correct about the former because I ended up becoming so engaged in the course that turning out “A” level work every week was easy. I was thinking about philosophy all the time. Runaway trolleys sped through my head, and internal, heated arguments with myself took the place of singing in the dorm showers. All this is due to learning through conversation.

A certain professor is to thank for this.1 Each seventy-five minute period, he taught us through conversation. He never gave us the answers for free, but instead made us mentally work to get closer to our truth. In this way, he drew in the mysterious elements of conversation and not knowing until you ask, making each answer like solving a riddle. This served two main purposes: firstly, it helped me to feel as though I really earned an answer when I found one. This style of learning was novel to me, and strayed so much from the way I had been conditioned to learn in the past, which was mostly frantically copying notes. Secondly, it reinforced my confidence in myself as a learner.

I’ll add one more: it made each class period feel as though it lasted ten minutes.

—-

Teresa Nelson is an Undergraduate Assistant at the Center for Ethics & Education.

Listen to the “Learning Through Conversation” episode.

News & Events

John Dewey Society Webinar on technology: Friday, February 23, 204

EdEthics course on writing case studies: begins March 4, 2024

NAAPE call for proposals: due July 1, 2024

The professor Teresa mentions is Harry Brighouse.